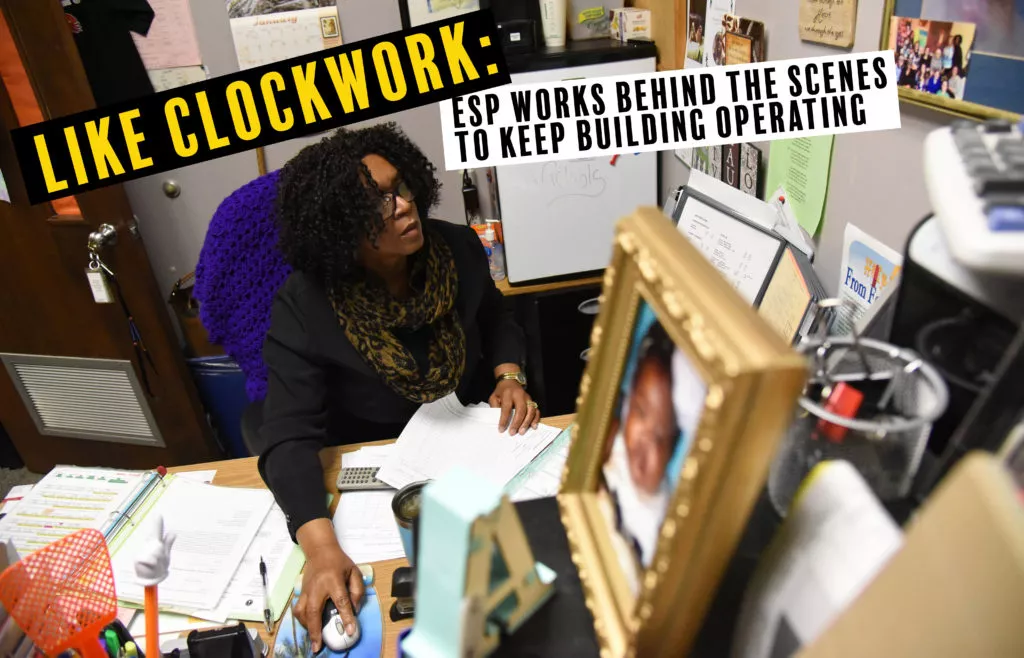

Audrey Nichols is a morning person. That’s pretty much a job requirement for Nichols, who has been the office bookkeeper at Landmark Elementary for nearly twenty years. From the moment the children arrive, Nichols is thrown into a whirlwind of logistical triage. She’s greeting the students with hugs and encouragement, figuring out which teachers need subs, adjusting the fill-in schedule on the fly, making sure there are staff members on duty where they need to be, unlocking doors, answering phone calls, ensuring that children in need of medicine are taken care of, stopping in the hallway to correct misbehaviors or give cheerful pep talks, handling any influx of visitors or work orders, and solving problems wherever they pop up in the building.

“That little clause that says other duties as assigned,” she says with a laugh. “They’re not really assigned, they just kind of fall on you, because it has to be done!”

Picture a school and your first thought is probably a teacher engaging students in a classroom, or perhaps the buzz of activity in the cafeteria, or the energy of an assembly in the auditorium. But none of that would be possible without the coordination and communal spirit in the building’s heart and hub: the school office. In countless ways, out in the hallways and behind the scenes, Nichols is the cog that makes the school days at Landmark hum along smoothly.

“It’s a job with many hats, a multi-tasking job, but I love it,” Nichols says. “Just being able to know that everybody’s happy is my main goal. Every teacher has what they need, every child has what they need, and every parent has an answer to their questions.”

The seed was planted for Nichols’ interest in becoming an education support professional (ESP) when she was a high-school student herself, in Arkadelphia.

“When I think back to the role of support staff when I was in school, they all played a major part,” Nichols says. “They were always willing to go that extra mile for kids. Everybody was on the same page, it was about educating our kids and that made a world of difference in my life.”

In fact, the ESP who had the biggest impact on Nichols held the same job that Nichols holds today. “Mary Hill, the young lady who worked in the office, was someone I really looked up to,” Nichols remembers. “She ran that place! In my world, the school was all about her. I said, ‘I can do that, I would love to do that.’ She was one of those people who was like a mother hen. There was no child who did without, because she was always there, always present, always willing to go that extra mile for us. If you had a problem, you could go to the office and talk to Ms. Hill. She always had a kind smile for you, a kind word.”

Like her mentor Ms. Hill, Nichols does much more than making sure the bills are paid, taking an active role in shaping the lives of students, as well as outreach to parents and the community.

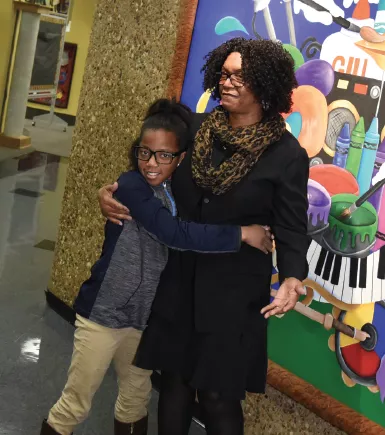

“So many of the kids, all they want is for somebody to give them a smile, ask how their day is,” she says. “If somebody needs a hug, I’m there. When they come in to the office, if there’s an issue, they know they can talk to me. The kids know that I’ll go out of my way to help them and that’s important to them.”

Nichols’ office is covered wall-to-wall in photos, notes, and drawings from current and former students, and every one of them has a story. One former student, now in junior high, used to walk down the hallways unhappily until Nichols pulled her aside.

“She would tell me, ‘I hate school,” Nichols recalls. “I said, ‘oh baby, that’s not what I want to hear.’ So she became my project for that year. After that first conversation, she wrote me a poem. I told her, ‘you’ve got a gift. I need a poem every day.’ After that, she wrote me a poem every day, and never missed a day at school.

“She was a very smart child but she wasn’t pushing herself. And then I saw her blossom, her grades went up, she became more outgoing and positive, and school became more interesting to her.”

Nichols kept encouraging her to write those daily poems and still has all of them today. She never throws anything students give her away, and every single item serves as a symbol of a connection that Nichols has made. As is often the case, the family kept in touch even after the student left Landmark; when she was in junior high, her mother called Nichols to say that she was acting up in school again.

“I said okay, I’ll go and talk to her,” Nichols says. “And that’s all she wanted--she said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you to call me!’”

One of Nichols’ passion projects at Landmark has been helping to lead an annual fourth-grade field trip. Leaving Wednesday night and returning on Saturday, the students take a charter bus to the Gulf Coast in Mississippi, for educational activities in the water and the classroom at the University of Southern Mississippi.

“It’s just something they talk about forever,” Nichols says. “They learn about estuaries, have classes out on the beach, take a boat ride out to the Gulf. They’ve dissected squid and cooked calamari, they’ve seen dolphins and sharks and sea turtles. I have done it every year and every year I’ve learned something.

“It’s totally fun and instructional, and it brings them life skills. They get a chance to learn to be independent, to spend the night in the dormitories where the college students live and eat in the cafeteria where the college students eat. It’s become like a rite of passage.”

Nichols also takes a leadership role with Landmark’s Backpacks for Kids program, providing nutritious food for students in need to take home over the weekend, as well as taking students with special needs to the Special Olympics, which she has been actively involved with for more than 20 years ever since her own son, who has Down Syndrome, first participated.

In addition to her work at Landmark, Nichols has been active in AEA and NEA. She is in her seventh year serving in the AEA governance, working on multiple committees, and she helps lead NEA trainings around the country. She is particularly passionate about her role on the NEA Bullying and Sexual Harassment Prevention and Intervention cadre.

“I tell the kids in this building that it’s very important that we don’t bully because if you start out now bullying then you continue on and become an adult bully, and those are dangerous,” she says. “And we teach the adults how to intervene in those situations.”

Nichols is also on the state and national Every Student Succeeds Act teams, giving her the opportunity to be a voice for ESPs and for the community.

“It took somebody pulling me along and telling me, ‘I see something in you,’” Nichols says. “AEA has afforded me opportunities to be in leadership and it makes me understand more clearly the workings of what’s going on. Our communities and our families are left out of the education loop. AEA and NEA have empowered me to ask questions and buck against the system if I don’t think it’s right. I’m supposed to se be an advocate—that’s where I see myself.”

Interacting with other educators nationally has provided Nichols with ideas and resources that she has brought back to Landmark.

“I come home and share with my administrator, talk to my teachers, and I talk to parents about it,” she says. “We’re always thinking about pushing our kids forward.”

Nichols sees a special value in her involvement in leadership and training roles as an ESP.

“I’m always saying ‘educator,’ stop just saying ‘teacher,’” she says. “When you say educator, you’re inclusive of everybody. And my mantra is, it takes a village. It truly does. It takes us all to educate a student.”